- October 19, 2020

- by:

- in: Blog

Social media platforms have repeatedly found themselves in the United States government’s crosshairs over the last few years, as it has been progressively revealed just how much power they really wield, and to what purposes they’ve chosen to wield it. But unlike, say, a firearm or drug manufacturer, there is no designated authority who says

Social media platforms have repeatedly found themselves in the United States government’s crosshairs over the last few years, as it has been progressively revealed just how much power they really wield, and to what purposes they’ve chosen to wield it. But unlike, say, a firearm or drug manufacturer, there is no designated authority who says what these platforms can and can’t do. So who regulates them? You might say everyone and no one.

Now, it must be made clear at the outset that these companies are by no means “unregulated,” in that no legal business in this country is unregulated. For instance Facebook, certainly a social media company, received a record $5 billion fine last year for failure to comply with rules set by the FTC. But not because the company violated its social media regulations — there aren’t any.

Facebook and others are bound by the same rules that most companies must follow, such as generally agreed-upon definitions of fair business practices, truth in advertising, and so on. But industries like medicine, energy, alcohol, and automotive have additional rules, indeed entire agencies, specific to them; Not so social media companies.

I say “social media” rather than “tech” because the latter is much too broad a concept to have a single regulator. Although Google and Amazon (and Airbnb, and Uber, and so on) need new regulation as well, they may require a different specialist, like an algorithmic accountability office or online retail antitrust commission. (Inasmuch as tech companies act within regulated industries, such as Google in broadband, they are already regulated as such.)

Social media can roughly defined as platforms where people sign up to communicate and share messages and media, and that’s quite broad enough already without adding in things like ad marketplaces, competition quashing and other serious issues.

Who, then, regulates these social media companies? For the purposes of the U.S., there are four main directions from which meaningful limitations or policing may emerge, but each one has serious limitations, and none was actually created for the task.

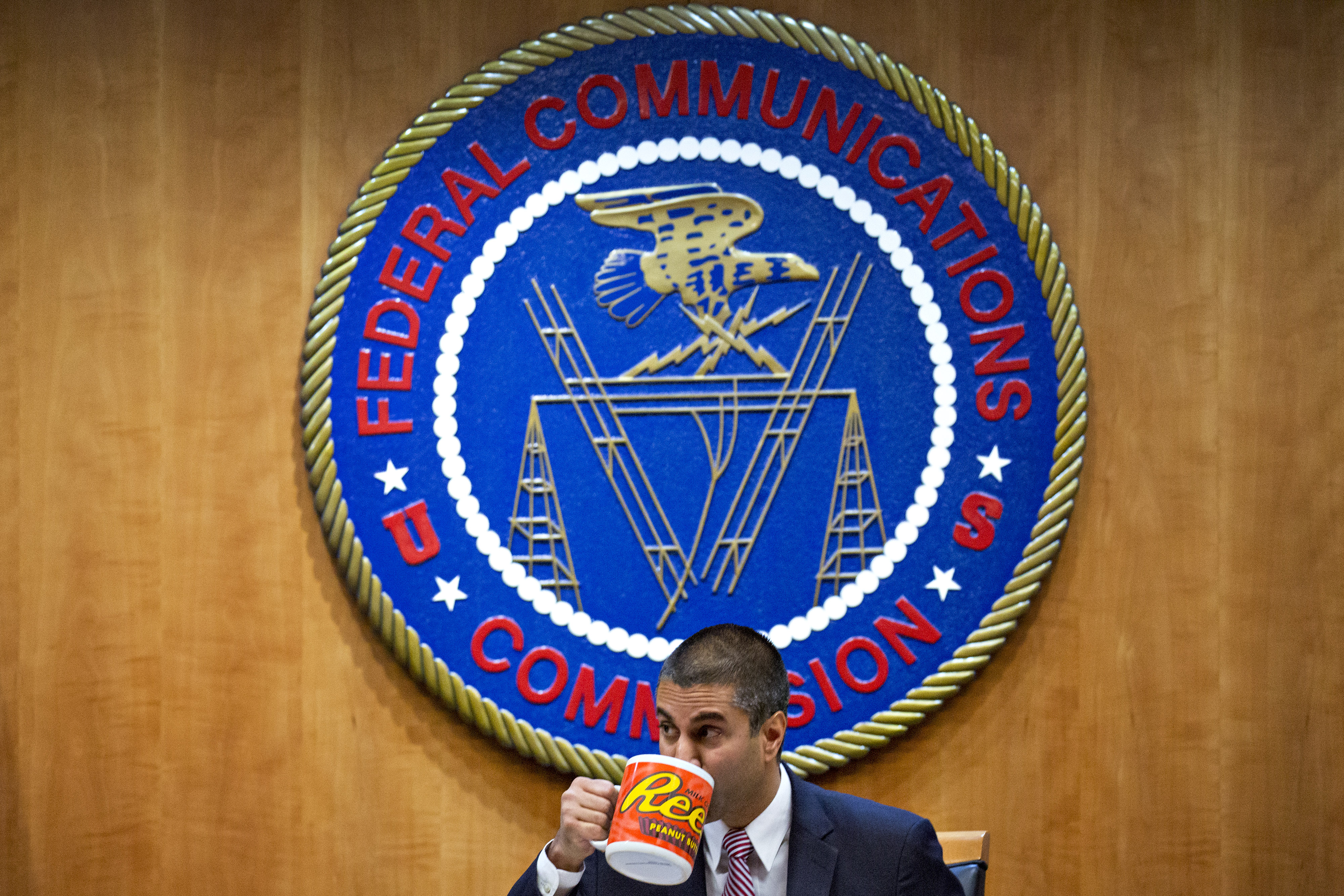

1. Federal regulators

Image Credits: Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg

The Federal Communications Commission and Federal Trade Commission are what people tend to think of when “social media” and “regulation” are used in a sentence together. But one is a specialist — not the right kind, unfortunately — and the other a generalist.

The FCC, unsurprisingly, is primarily concerned with communication, but due to the laws that created it and grant it authority, it has almost no authority over what is being communicated. The sabotage of net neutrality has complicated this somewhat, but even the faction of the Commission dedicated to the backwards stance adopted during this administration has not argued that the messages and media you post are subject to their authority. They have indeed called for regulation of social media and big tech — but are for the most part unwilling and unable to do so themselves.

The Commission’s mandate is explicitly the cultivation of a robust and equitable communications infrastructure, which these days primarily means fixed and mobile broadband (though increasingly satellite services as well). The applications and businesses that use that broadband, though they may be affected by the FCC’s decisions, are generally speaking none of the agency’s business, and it has repeatedly said so.

The only potentially relevant exception is the much-discussed Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act (an amendment to the sprawling Communications Act), which waives liability for companies when illegal content is posted to their platforms, as long as those companies make a “good faith” effort to remove it in accordance with the law.

But this part of the law doesn’t actually grant the FCC authority over those companies or define good faith, and there’s an enormous risk of stepping into unconstitutional territory, because a government agency telling a company what content it must keep up or take down runs full speed into the First Amendment. That’s why although many think Section 230 ought to be revisited, few take Trump’s feeble executive actions along these lines seriously.

The agency did announce that it will be reviewing the prevailing interpretation of Section 230, but until there is some kind of established statutory authority or Congress-mandated mission for the FCC to look into social media companies, it simply can’t.

The FTC is a different story. As watchdog over business practices at large, it has a similar responsibility towards Twitter as it does towards Nabisco. It doesn’t have rules about what a social media company can or can’t do any more than it has rules about how many flavors of Cheez-It there should be. (There are industry-specific “guidelines” but these are more advisory about how general rules have been interpreted.)

On the other hand, the FTC is very much the force that comes into play should Facebook misrepresent how it shares user data, or Nabisco overstate the amount of real cheese in its crackers. The agency’s most relevant responsibility to the social media world is that of enforcing the truthfulness of material claims.

You can thank the FTC for the now-familiar, carefully worded statements that avoid any real claims or responsibilities: “We take security very seriously” and “we think we have the best method” and that sort of thing — so pretty much everything that Mark Zuckerberg says. Companies and executives are trained to do this to avoid tangling with the FTC: “Taking security seriously” isn’t enforceable, but saying “user data is never shared” certainly is.

In some cases this can still have an effect, as in the $5 billion fine recently dropped into Facebook’s lap (though for many reasons that was actually not very consequential). It’s important to understand that the fine was for breaking binding promises the company had made — not for violating some kind of social-media-specific regulations, because again, there really aren’t any.

The last point worth noting is that the FTC is a reactive agency. Although it certainly has guidelines on the limits of legal behavior, it doesn’t have rules that when violated result in a statutory fine or charges. Instead, complaints filter up through its many reporting systems and it builds a case against a company, often with the help of the Justice Department. That makes it slow to respond compared with the lightning-fast tech industry, and the companies or victims involved may have moved beyond the point of crisis while a complaint is being formalized there. Equifax’s historic breach and minimal consequences are an instructive case:

So: While the FCC and FTC do provide important guardrails for the social media industry, it would not be accurate to say they are its regulators.

2. State legislators

States are increasingly battlegrounds for the frontiers of tech, including social media companies. This is likely due to frustration with partisan gridlock in Congress that has left serious problems unaddressed for years or decades. Two good examples of states that lost their patience are California’s new privacy rules and Illinois’s Biometric Information Privacy Act (BIPA).

The California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) was arguably born out the ashes of other attempts at a national level to make companies more transparent about their data collection policies, like the ill-fated Broadband Privacy Act.

Californian officials decided that if the feds weren’t going to step up, there was no reason the state shouldn’t at least look after its own. By convention, state laws that offer consumer protections are generally given priority over weaker federal laws — this is so a state isn’t prohibited from taking measures for their citizens’ safety while the slower machinery of Congress grinds along.

The resulting law, very briefly stated, creates formal requirements for disclosures of data collection, methods for opting out of them, and also grants authority for enforcing those laws. The rules may seem like common sense when you read them, but they’re pretty far out there compared to the relative freedom tech and social media companies enjoyed previously. Unsurprisingly, they have vocally opposed the CCPA.

BIPA has a somewhat similar origin, in that a particularly far-sighted state legislature created a set of rules in 2008 limiting companies’ collection and use of biometric data like fingerprints and facial recognition. It has proven to be a huge thorn in the side of Facebook, Microsoft, Amazon, Google, and others that have taken for granted the ability to analyze a user’s biological metrics and use them for pretty much whatever they want.

Many lawsuits have been filed alleging violations of BIPA, and while few have produced notable punishments like this one, they have been invaluable in forcing the companies to admit on the record exactly what they’re doing, and how. Sometimes it’s quite surprising! The optics are terrible, and tech companies have lobbied (fortunately, with little success) to have the law replaced or weakened.

What’s crucially important about both of these laws is that they force companies to, in essence, choose between universally meeting a new, higher standard for something like privacy, or establishing a tiered system whereby some users get more privacy than others. The thing about the latter choice is that once people learn that users in Illinois and California are getting “special treatment,” they start asking why Mainers or Puerto Ricans aren’t getting it as well.

In this way state laws exert outsize influence, forcing companies to make changes nationally or globally because of decisions that technically only apply to a small subset of their users. You may think of these states as being activists (especially if their attorneys general are proactive), or simply ahead of the curve, but either way they are making their mark.

This is not ideal, however, because taken to the extreme, it produces a patchwork of state laws created by local authorities that may conflict with one another or embody different priorities. That, at least, is the doomsday scenario predicted almost universally by companies in a position to lose out.

State laws act as a test bed for new policies, but tend to only emerge when movement at the federal level is too slow. Although they may hit the bullseye now and again, like with BIPA, it would be unwise to rely on a single state or any combination among them to miraculously produce, like so many simian legislators banging on typewriters, a comprehensive regulatory structure for social media. Unfortunately, that leads us to Congress.

3. Congress

Image: Bryce Durbin/TechCrunch

What can be said about the ineffectiveness of Congress that has not already been said, again and again? Even in the best of times few would trust these people to establish reasonable, clear rules that reflect reality. Congress simply is not the right tool for the job, because of its stubborn and willful ignorance on almost all issues of technology and social media, its countless conflicts of interest, and its painful sluggishness — sorry, deliberation — in actually writing and passing any bills, let alone good ones.

Companies oppose state laws like the CCPA while calling for national rules because they know that it will take forever and there’s more opportunity to get their finger in the pie before it’s baked. National rules, in addition to coming far too late, are much more likely also be watered down and riddled with loopholes by industry lobbyists. (This is indicative of the influence these companies wield over their own regulation, but it’s hardly official.)

But Congress isn’t a total loss. In moments of clarity it has established expert agencies like those in the first item, which have Congressional oversight but are otherwise independent, empowered to make rules, and kept technically — if somewhat limply — nonpartisan.

Unfortunately, the question of social media regulation is too recent for Congress to have empowered a specialist agency to address it. Social media companies don’t fit neatly into any of the categories that existing specialists regulate, something that is plainly evident by the present attempt to stretch Section 230 beyond the breaking point just to put someone on the beat.

Laws at the federal level are not to be relied on for regulation of this fast-moving industry, as the current state of things shows more than adequately. And until a dedicated expert agency or something like it is formed, it’s unlikely that anything spawned on Capitol Hill will do much to hold back the Facebooks of the world.

4. European regulators

Of course, however central it considers itself to be, the U.S. is only a part of a global ecosystem of various and shifting priorities, leaders, and legal systems. But in a sort of inside-out version of state laws punching above their weight, laws that affect a huge part of the world except the U.S. can still have a major effect on how companies operate here.

Of course, however central it considers itself to be, the U.S. is only a part of a global ecosystem of various and shifting priorities, leaders, and legal systems. But in a sort of inside-out version of state laws punching above their weight, laws that affect a huge part of the world except the U.S. can still have a major effect on how companies operate here.

The most obvious example is the General Data Protection Regulation or GDPR, a set of rules, or rather augmentation of existing rules dating to 1995, that has begun to change the way some social media companies do business.

But this is only the latest step in a fantastically complex, decades-long process that must harmonize the national laws and needs of the E.U. member states in order to provide the clout it needs to compel adherence to the international rules. Red tape seldom bothers tech companies, which rely on bottomless pockets to plow through or in-born agility to dance away.

Although the tortoise may eventually in this case overtake the hare in some ways, at present the GDPR’s primary hindrance is not merely the complexity of its rules, but the lack of decisive enforcement of them. Each country’s Data Protection Agency acts as a node in a network that must reach consensus in order to bring the hammer down, a process that grinds slow and exceedingly fine.

When the blow finally lands, though, it may be a heavy one, outlawing entire practices at an industry-wide level rather than simply extracting pecuniary penalties these immensely rich entities can shrug off. There is space for optimism as cases escalate and involve heavy hitters like antitrust laws in efforts that grow to encompass the entire “big tech” ecosystem.

The rich tapestry of European regulations is really too complex of a topic to address here in the detail it deserves, and also reaches beyond the question of who exactly regulates social media. Europe’s role in that question of, if you will, speaking slowly and carrying a big stick promises to produce results on a grand scale, but for the purposes of this article it cannot really be considered an effective policing body.

(TechCrunch’s E.U. regulatory maven Natasha Lomas contributed to this section.)

5. No one? Really?

As you can see, the regulatory ecosystem in which social media swims is more or less free of predators. The most dangerous are the small, agile ones — state legislatures — that can take a bite before the platforms have had a chance to brace for it. The other regulators are either too slow, too compromised, or too involved (or some combination of the three) to pose a real threat. For this reason it may be necessary to introduce a new, but familiar, species: the expert agency.

As noted above, the FCC is the most familiar example of one of these, though its role is so fragmented that one could be forgiven for forgetting that it was originally created to ensure the integrity of the telephone and telegraph system. Why, then, is it the expert agency for orbital debris? That’s a story for another time.

Image Credit: Bryce Durbin/TechCrunch

What is clearly needed is the establishment of an independent expert agency or commission in the U.S., at the federal level, that has statutory authority to create and enforce rules pertaining to the handling of consumer data by social media platforms.

Like the FCC (and somewhat like the E.U.’s DPAs), this should be officially nonpartisan — though like the FCC it will almost certainly vacillate in its allegiance — and should have specific mandates on what it can and can’t do. For instance, it would be improper and unconstitutional for such an agency to say this or that topic of speech should be disallowed from Facebook or Twitter. But it would be able to say that companies need to have a reasonable and accessible definition of the speech they forbid, and likewise a process for auditing and contesting takedowns. (The details of how such an agency would be formed and shaped is well beyond the scope of this article.)

Even the likes of the FAA lags behind industry changes, such as the upsurge in drones that necessitated a hasty revisit of existing rules, or the huge increase in commercial space launches. But that’s a feature, not a bug. These agencies are designed not to act unilaterally based on the wisdom and experience of their leaders, but are required to perform or solicit research, consult with the public and industry alike, and create evidence-based policies involving, or at least addressing, a minimum of sufficiently objective data.

Sure, that didn’t really work with net neutrality, but I think you’ll find that industries have been unwilling to capitalize on this temporary abdication of authority by the FCC because they see that the Commission’s current makeup is fighting a losing battle against voluminous evidence, public opinion, and common sense. They see the writing on the wall and understand that under this system it can no longer be ignored.

With an analogous authority for social media, the evidence could be made public, the intentions for regulation plain, and the shareholders — that is to say, users — could make their opinions known in a public forum that isn’t owned and operated by the very companies they aim to rein in.

Without such an authority these companies and their activities — the scope of which we have only the faintest clue to — will remain in a blissful limbo, picking and choosing by which rules to abide and against which to fulminate and lobby. We must help them decide, and weigh our own priorities against theirs. They have already abused the naive trust of their users across the globe — perhaps it’s time we asked them to trust us for once.