- August 12, 2021

- by:

- in: Blog

If you’ve ever sold a house, you know what a pain it is to go through the process of listing, showing and negotiating the sale of your home. It’s so much of a pain that many people put it off as long as possible because they don’t want to deal with it. The result is

If you’ve ever sold a house, you know what a pain it is to go through the process of listing, showing and negotiating the sale of your home.

It’s so much of a pain that many people put it off as long as possible because they don’t want to deal with it. The result is fewer homes on the market, which exacerbates existing housing shortages in already tight markets such as the San Francisco Bay Area.

In an attempt to help address the problem, one startup called Aalto has built out a new kind of homeowner marketplace. It’s a private one that doesn’t rely on the MLS, and gives sellers more control of how and when their homes are listed, shown and sold. Today Aalto is emerging from stealth and announcing that it has raised $13 million in a Series A funding round led by Sequoia Capital.

Background Capital, Defy Partners, Maple VC and Greg Waldorf — the first investor at Trulia — also participated in the financing, which brings Aalto’s total raised to $17.3 million since its 2018 inception.

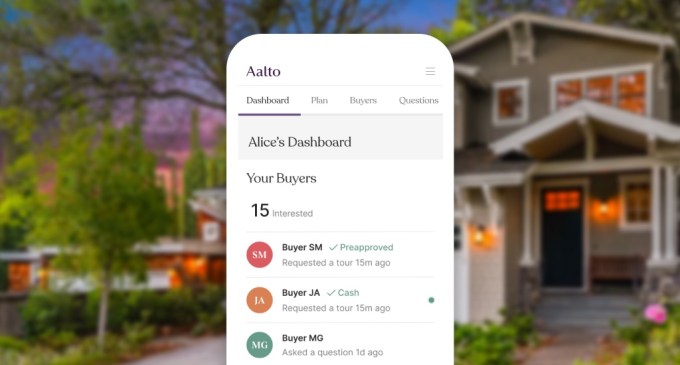

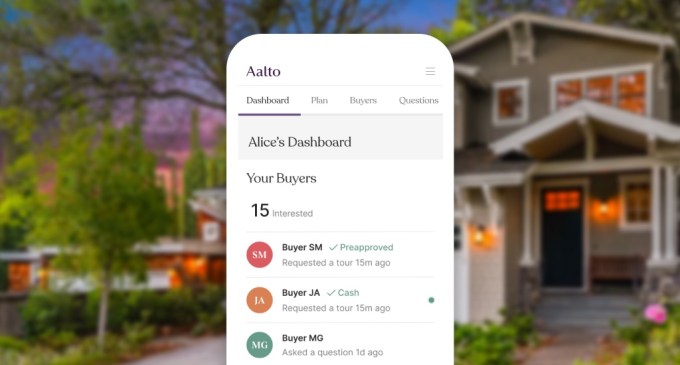

Aalto’s online marketplace, which launched in April of this year, directly connects homeowners to buyers. The company claims that a potential seller can list their home on its platform in five minutes, rather than a typical process that is closer to five weeks. Since launching in the Bay Area, Aalto has built up a network of more than 30,000 buyers and more than two dozen homes have been sold via the marketplace. Currently, about 85 homes are listed for sale on its platform, with an average of one new home being added per day.

Ironically, Aalto founder and CEO Nick Narodny is the son and brother of real estate agents. He concedes that the startup’s platform could be seen as a threat to the industry, but notes the trade-off is that more homes end up on the market, which helps minimize the region’s affordability crisis, and sellers see higher returns.

Currently, 5-10% of total available inventory listed in competitive markets like Dublin, Fremont, Mill Valley and Milpitas are listed on the Aalto platform. And, Narodny said, the company is on its way to bring more homes to market, sooner.

“Buying or selling a home is one of the biggest events people will ever experience, but it’s also a tedious, outdated process,” he said.

Image Credits: Nick Narodny / Aalto

Aalto aims to double the number of homes on the market in the Bay Area by streamlining the way homeowners can list, without the third-parties or contracts required elsewhere. This dramatically lowers the bar to sell, according to Narodny, bringing homes to market an average of four and a half months earlier than traditional real estate processes.

The platform offers a preview listing feature that allows sellers to list with no commitment. They can also build a waitlist of qualified buyers for their home while they consider a sale.

“We pull the tax record and info to make it super easy and ask the seller to fill out a Q&A,” Narodny said. After filling out that info, sellers can then see interested buyers and those that are prequalified or that can make all cash offers.

The process is also less intrusive, Narodny said, by giving the seller more of a say in who sees their home and when. For example, sellers can also line up virtual or in-person showings on their own schedule. And they can sell the homes on their timelines — whether it be in a few weeks, or few months.

For example, a San Francisco-based hand surgeon recently listed his home on the Aalto platform with the desire of moving at the end of October. More than two dozen people were interested and he allowed a few people to tour the home. He was able to sell the house based on a timeline that was more beneficial for him.

“People can sell totally on their terms and are much more connected in the process,” Narodny said. Busy professionals such as the surgeon with director and above titles and growing families so far are among the most common sellers on the platform.

Image Credits: Aalto

Also, there is an economic benefit. By removing a middleman, or agent, from the process, sellers can make an average of $44,000 more on their home sale, according to Narodny. The startup charges a 1% fee, compared to the 2-2.5% commission that an agent charges. But if a seller requires help “with the hard stuff,” Aalto has “expert, licensed” people available.

Sellers can also craft descriptions of their homes in a way that comes across as more personal than if an agent does it, according to Narodny.

“We have them tell their own story of their home,” he said.

It also gives them more privacy. For example, an MLS will show when a home was listed and any price reductions. A home listed on Aalto won’t include any of that information. Also similar to Airbnb, the seller’s exact address is not shared, just a radius.

The benefit for buyers — besides having more options — is the ability to set up instant alerts, join waitlists and schedule showings in one easy-to-use platform. They can also “anonymously prequalify and share that with a seller,” Narodny said.

Bryan Schreier, partner at Sequoia Capital, believes that real estate is “one of the last giant industries with a 1900s experience.”

“It’s a painful process where the seller has limited visibility and the buyer is holding their breath after every bid,” he said. “Aalto is the first company to reinvent how homes are bought and sold by putting the consumer first. It goes far beyond a listing site and reinvents every aspect of the experience to be customer oriented rather than realtor oriented.”

Looking ahead, the company plans to expand beyond the Bay Area to other major metropolitan real estate markets in California and across the country. It also plans to use its new capital to continue improving its technology.

Meanwhile, Narodny insists that while the platform may be seen as a threat by some agents, it’s not a malicious thing.

“My family and I are very close. It’s something that I talk about with them quite a bit,” he told TechCrunch. “I believe Aalto truly is additive. We still work with them every day and will continue to…It’s not like agents are totally being replaced.”