Over the past five years, the Southeastern region, led by Atlanta, has gone from being “one of the best kept secrets” in tech, to a vibrant ecosystem teeming with a herd of the billion dollar tech businesses that are referred to in the investment world as “unicorns” (thanks to their supposed rarity). In those five

Over the past five years, the Southeastern region, led by Atlanta, has gone from being “one of the best kept secrets” in tech, to a vibrant ecosystem teeming with a herd of the billion dollar tech businesses that are referred to in the investment world as “unicorns” (thanks to their supposed rarity).

In those five years venture capital investments surged to $2.1 billion in the region, with $1 billion invested in the last year alone, according to Lisa Calhoun, a partner with the Atlanta based investment firm, Valor Ventures.

It’s indicative of the entrepreneurial talent coming from the network of private and public schools across the region like Georgia Tech, the University of Alabama, Auburn, the University of Georgia, Vanderbilt, Emory, and the historically black colleges and universities like Morehouse, Spelman, and Xavier. And it’s also a sign of a reinvestment in local entrepreneurship — a decades-long campaign to turn Atlanta into the center of a hub-and-spoke network of startup cities that spans Miami to Atlanta, with stops in Birmingham, Nashville, New Orleans,

“Atlanta is what a next generation, global, post-Silicon Valley tech hub looks like. Our demographics are ten years ahead of the U.S.’s transformation into a majority minority society,” wrote Calhoun in an email. “With over 40% of the U.S. population in the Southeast, the greatest density of founders and executives of color, rafts of tech companies like AirBnB locating here, and our own legacy of top tech and talent, Atlanta sets the tone for what’s next. We have the growing, diverse population base all strong founders need to scale.”

There’s still a lot of work to be done for the region to establish itself as one of the next engines of economic return for the venture capital and investment business, though.

“The Southeast is 24% of the US GDP, but only accounts for 7% of the venture investment,” noted Blake Patton, the founder and general partner of the Atlanta-based investment firm, Tech Square Ventures. “With the recent momentum in the region, that is changing and investors are taking notice and backing local managers who in turn are investing the region’s best and brightest entrepreneurs.”

The Internet boom and bust in Atlanta

In the years after the 1996 Olympics, Atlanta was a high-flying contender for the title of one of the next big startup hubs in the United States.

The Olympics had put the city on the world’s stage, and seeing the wave of activity, excitement, and investment that came with the advent of internet companies like Virginia’s America Online, Atlanta’s city council and mayor were making a push for the city to become a telecom and startup hub in the early days of the first Internet boom.

“Something happened in the mid-90s driven by the Olympics where Atlanta hit the map worldwide. It wasn’t just that we were a supply and logistics hub. In the late 90s as the dot-com boom really evolved, things happened underground that aren’t as transparent as they should be. Atlanta Gas Light had the largest dark fiber ring in the country surrounding Atlanta. That was built solely with the olympics in mind. We had Georgia Tech working on the next generation of aerospace, and they added computer engineering,” said Christy Brown, the founder of the Atlanta based non-profit Launchpad2X and a serial entrepreneur and executive with deep ties to the Atlanta ecosystem.

Atlanta also had its fair share of early successes — high flying telecom and networking companies that were critical to the evolution of the first dot com era whose later years were either mired in scandal or who were acquired by much larger entities. These are companies like MCI Worldcom and Airtouch Cellular, which was gobbled up by Singular Wireless and would eventually become part of a restructured AT&T.

“There were all kinds of tech things happening in the city. A lot of these founders were getting venture on paper which evolved into the dot-bomb,” said Brown. “All of this was happening mid to late nineties, when the dot-bomb happened there was a lot of failure in the Atlanta area.”

The implosion of early internet companies that came with the bursting of the dot-com bubble in 2000 reverberated through Atlanta’s tech ecosystem, erasing the early gains that companies made and setting the stage for a decade-long period of reconstruction punctuated by a few successes from holdouts that managed to make their way through the wreckage.

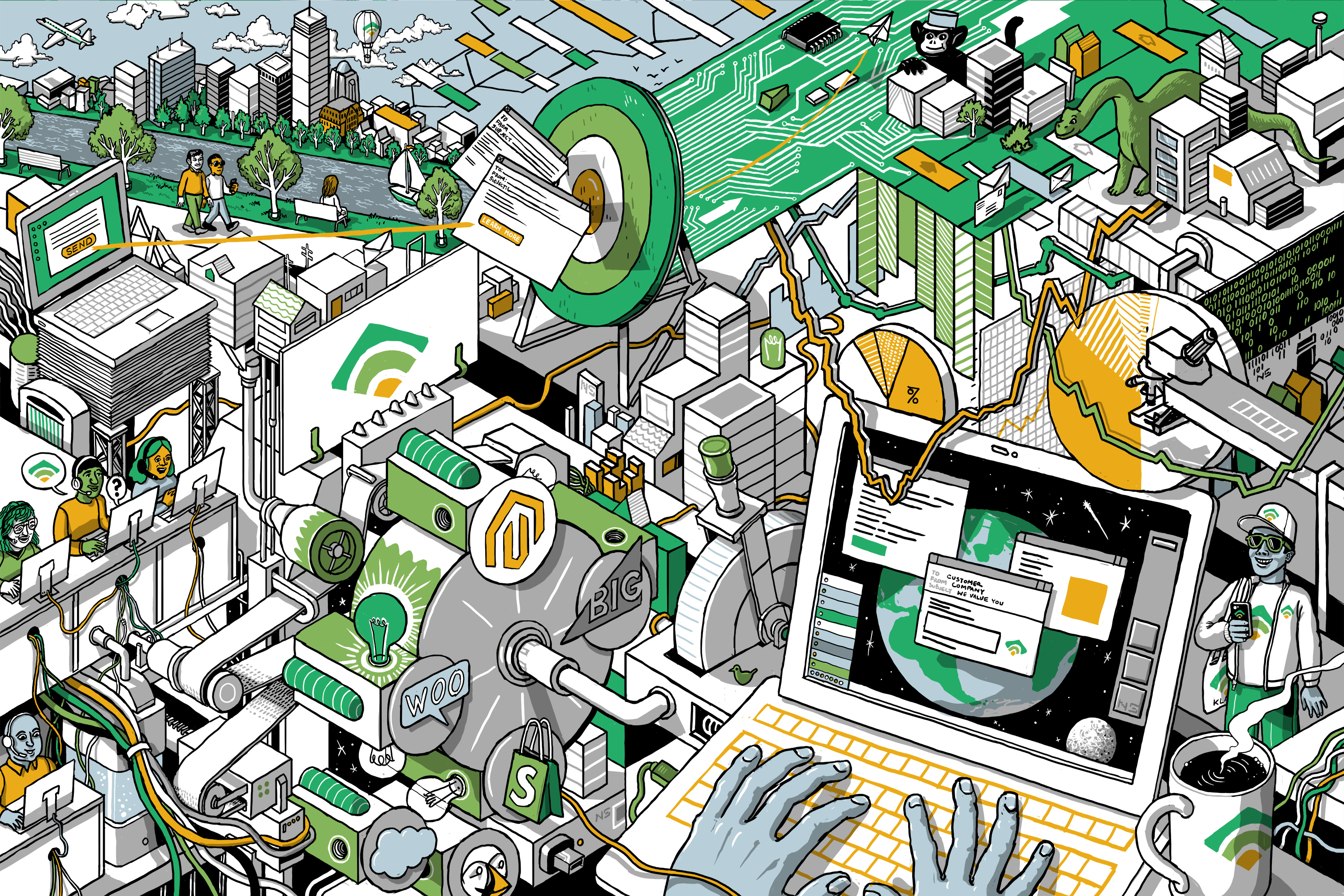

Image Credits: TechCrunch

Through the lean years

One of those companies was MailChimp. Launched in 2001, in the early aftermath of the bursting of the tech bubble, the privately held email marketing startup was one of a number of projects at Ben Chestnut’s and Dan Kurzius’ web development firm.

The two men met at Cox Interactive Media to work on an early MP3 product. When that fizzled both men eventually lost their jobs and went into business together. They built MailChimp off of revenue, bootstrapping the business without venture capital in a model that many other tech founders in the area would seek to replicate.

A few years later, in 2003, another entrepreneur named John Marshall began installing internet hotspots at hospitality businesses, eventually expanding his Wandering WiFi service to include monitoring and managing other kinds of network infrastructure. This foray into startup land would eventually create another big Atlanta tech exit in AirWatch.

For the first six years MailChimp remained a side hustle, a product that the two co-founders continued to work on, but didn’t devote themselves to full time. It wasn’t until 2007, when the service hit 10,000 users, that the company became the full-time job for both founders.

Their once-scrappy startup turned them into billionaires. A 2018 Forbes profile put the company’s valuation at $4.2 billion on roughly $600 million in revenue.

If there was a starting gun for the Atlanta tech renaissance, it might be 2006, a few years before the global financial crisis and a time when the broader tech industry was finding itself a less financially precarious prospect for investors. Internet Security Systems, an Atlanta area dot-com darling that held an initial public offering in the late 90s sold to IBM for $1.3 billion that year.

Tom Noonan and Chris Klaus, the co-founders at Internet Security Systems, had an equally long road. What had started out as a company built when Klaus lived above Noonan’s garage in Atlanta in the mid-90s, morphed into a company pulling in $400 million in annual revenue before its acquisition by IBM.

As capital started flowing into Atlanta and the city regained some of its footing in the tech world, founders who had exited their companies began to reinvest money locally. And the city moved to create more events to foster entrepreneurship. 2006 saw the launch of Venture Atlanta, a conference designed to showcase early talent and startups coming from the region that served as a launchpad for several entrepreneurs that would shape the future of the city’s technology industry.

Image Credits: TechCrunch

Setting a new scene

If 2006 was a big year for exits in Atlanta, it also proved to be the year that opened the floodgates on new entrepreneurial activity, which would give rise over the next decade to what’s now a thriving startup scene, pumping out a record number of billion dollar tech businesses.

It was the year that David Cummings and Adam Blitzer founded Pardot, a marketing and sales automation software developer that grew quickly and attracted the attention of big industry players like ExactTarget. It was also the year that Manhattan Associates executive Alan Dabbiere joined Marshall and Wandering WiFi became AirWatch, a company providing management and security tech for mobile enterprise networks.

Over the next few years MailChimp would become more active; Cloud Sherpas, founded by the entrepreneurs Michael Cohn and Sean O’Brien (who are now founders of the investment firm Overline Ventures) would launch and so would companies like the video streaming tech developer, ClearLeap (bought by IBM in 2015 and valued at over $110 million); the security company Damballa would launch (later acquired by Atlanta neighbor Core Security); and the service powering many of the major banks customer rewards programs, Cardlytics (now trading on the Nasdaq with a $4 billion market cap).

Buoyed by these emerging tech companies, other entrepreneurs would join the fray, with Kabbage (acquired for $850 million), Calendly (a $3 billion business as of this year) and the voice identification technology developer Pindrop (which raised $90 million back in 2018) emerging onto the scene at around the same time.

These companies set the table for what would become a buffet of startups focused primarily on payments and financial services, cloud-based business solutions, and internet security. Gone were the hardware heavy telecom companies and networking companies like Scientific Atlanta, whose business is compared to Hewlett Packard for having brought a high tech industry to the city in the 1950s — much like HP did in Silicon Valley.

Meanwhile, a new generation of investor was moving into the Atlanta orbit, presaged by the 2006 launch of BIP Capital — an event that also proved meaningful for the city’s budding entrepreneurs.

Staking claims for Atlanta’s future

The rising tide of entrepreneurs coming out of Atlanta also served to revitalize the city’s moribund investment community. Hit hard by the bursting of the dot-com bubble, the Atlanta-area firms that managed to survive the crash began to look to later stage businesses and outside of the Atlanta tech ecosystem for startups to back, according to data from CrunchBase and several interviews with investors and founders.

Noro-Moseley Partners, for instance, is by far the most active investor hailing from Atlanta. Over it’s long history the firm has done over 123 deals according to Crunchbase, but in the last five years, data indicates only four investment from the firm were made into Atlanta-based companies.

By contrast, the arrivistes at BIP have been deploying capital and raising successively larger funds since they first came to town. Over the last five years the firm has invested in at least 15 Atlanta-area deals, and now, under the moniker of Panoramic Ventures, the firm is targeting a $300 million early stage fund to invest across the southeast and midwest.

“Traditionally, access to capital was challenging for founders in Atlanta and the Southeast. In the past, it was considered a disadvantage for a tech business to be based outside of the traditional innovation hubs [in] Silicon Valley or the Northeast because it was more difficult to secure investment capital. This was because the large funds were located inside the hubs and had plenty of opportunities right on their doorsteps for investment,” wrote Mark Buffington, the co-founder and chief executive of BIP Capital, in an email to TechCrunch. “While the traditional hubs are still key in terms of aggregate capital, the requirement for startups to also be inside the hubs has changed. Increasingly, venture funds are locating themselves in other areas of the country where innovation is occurring. At the same time, the amount of capital available from local and regional investors is growing, in large part due to the influx of dollars into the private markets.”

Another member of the new school of investors that’s changing Atlanta’s investment scene is Patton; whose work with Tech Square Ventures and Engage, the corporate venture capital investment firm and startup initiative harnessing the power of a number of the biggest companies in Atlanta, also galvanized entrepreneurship and the newfound interest in startup tech companies.

“The recent momentum in the region is driven by increased connectivity across the innovation ecosystem and a critical mass of entrepreneurs and talent coming out of the region’s many successful startups. With corporations focused on digital transformation and innovation, all large companies have to a degree become tech companies and that drives connectivity as talent moves across both startups and tech companies,” Patton said. “Perhaps our greatest strength is our diversity and being home to four leading HBCUs, and I hope in the next 5 years the Southeast will emerge as a leader in producing successful startups founded by diverse entrepreneurs and built with diverse teams. It’s not just a moral imperative – with half the nation’s black population, the Southeast must succeed in engaging under-served entrepreneurs to lead – and you can’t tackle diversity nationally without tackling it in the Southeast.”

Still, other ingredients were needed for the resurgence of startup activity in the city. These would be co-workings spaces like David Cummings’ launch of the Atlanta Tech Village in 2012; the continuing relevance of the Atlanta Tech Development Center; the Venture Atlanta conference and the co-working space around Hypepotamus — which remains the go-to publication for Southern startup activity.

Every entrepreneur and investor mentioned Cummings’ decision to reinvest in the city and launch the Tech Village near Atlanta’s tony suburb of Buckhead as one of the biggest sparks for the city’s renewed entrepreneurial fervor. Soon after Cummings sold Pardot he and David Lightburn established Atlanta Tech Village as a co-working spot for entrepreneurs. It attracted a number of new startup founders whose businesses would become the next wave of big startups. “When David Cummings sold Pardot he wanted a place for entrepreneurs to have community,” said one longtime player in the Atlanta tech community. “They would do these startup chow down lunches and really support entrepreneurs building businesses.”

And just as key was the longtime hub for Georgia Tech-affiliated startups, the Atlanta Tech Development Center, the entrepreneurs and investors noted. Venture Atlanta had a role to play as well, bringing investors from every corner of the country to the city to showcase top talent. Together with CreateX, and the Venture Atlanta program, the four initiatives and workspaces for early stage entrepreneurs planted a number of seeds that would soon blossom into companies like PartPic, Greenlight Financial (which is now worth $2.3 billion), Kabbage, FullStory and Pindrop.

Image Credits: TechCrunch

A haven for diverse founders and investors

During those early days of the Atlanta startup ecosystem, there was one spot more welcoming than most for diverse and women-led founders — the co-working space and offices for Hypepotamus.

Serial entrepreneur Monique Mills was there. So was Jewel Burks Solomon, who sold her company, PartPic, to Amazon in 2016 and is now the Head of Google for Startups in the U.S.

“My first office was at Hypepotamus because they offered free space,” Burks Solomon recalled. “And at the time I didn’t have much money. Then when I raised some money the next major one was at ATDC — the state of Georgia’s incubator. They offered subsidized space and they had an entrepreneur in residence and they had a whole program to help Atlanta-based startups with some kind of technology.”

It was the Hypepotamus space, and subsequent venues like Opportunity Hub and The Gathering Spot that catalyzed the Black entrepreneurial community in Atlanta, according to several founders and investors.

And if the Hypepotamus space, carved out by National Builder Supply, was one of the catalysts, then the angel investor, Mike Ross, was the other.

“Mike has funded many successful Black-led startups in the Atlanta ecosystem and we wouldn’t be where we are today without him,” entrepreneur Candace Mitchell Harris told UrbanGeekz in a recent profile. “When many have faced the run around of false promises or flat out rejections, Mike confidently put his money in and pushed our founders further.”

Ross, a Morehouse College alumnus, who made his wealth as a consultant in the construction and contracting industry has backed Black founders and investors including: Luma, Partpic, Monsieur, Axis Replay, Myavana, TechSquare Labs, Opportunity Hub, and The Gathering Spot.

Investors like Paul Judge and entrepreneurs like Joey Womack, Barry Givens, and Mitchell Harris, all benefited from Ross’ investment largesse.

“Mike was the catalyst for our company’s success as our very first angel investor,” says Mitchell Harris, co-founder and CEO of beauty tech startup Myavana, told UrbanGeekz. “I still remember meeting him for the first time at the Black Founders Conference in June 2012, inquisitive and eager to get behind the movement that was beginning in Atlanta in the tech startup scene.”

And Ross blazed a trail for other investors like the Fearless Fund, a group of women investors led by Arian Simone, Ayanna Parsons, and Keshia Knight Pulliam, who launched their first fund in 2019, and Collab Capital, which launched last year (and is led by Burks Solomon, Justin Dawkins, and Barry Givens) — close to a decade after Ross first began investing.

“Right now women of color are the most founded but the least funded entrepreneurs,” Simone said. “Atlanta is a mecca of black entrepreneurship for us to have a venture capital and tech presence here.. I will charge the city of Atlanta and the state of Georgia and the banks that they need to back what we’re doing here.. It is needed.”

Not only is it needed, but it’s working. Of the 36 venture capital firms identified as part of TechCrunch’s research as having a focus on early stage investments in the Atlanta area, 41% met one or more of the following criteria: identification as having a diversity focus across investments, identification as having a diverse fund management team, or both, according to data from Crunchbase.

And through a sample size of 158 startups spanning Pre-Seed, Seed, or Series A in the Atlanta area, which were included in TechCrunch’s research, 48% met one or more of the following criteria: identification as having a sex-diverse founding team, identification has having a racially-diverse founding team, or both. In many instances, founding teams did not self identify, so the number of diverse founders may be greater than currently documented based on publicly available data.

As UrbanGeekz noted, about 25% of the employees in Atlanta’s tech industry are black. In San Francisco, by contrast, that figure is 6%.

“Ten years ago [the Black tech startup ecosystem] was just starting out,” Ross told UrbanGeekz. “Now Atlanta is one of the top tech hubs in the country and the ecosystem is probably one of the most diverse.”

Looking ahead

“I’m really excited about what’s happening now. It’s much more diverse in terms of the people that have the ability to deploy capital. I’m optimistic about what is to come in the tech space,” said Burks Solomon.

She’s not alone. New firms like Cohn and O’Brien’s Overline Ventures, Panoramic, and Outlander Labs, the firm launched by the former Los Angeles investors Paige and Leura Craig are all signs of investors’ long-term belief in the health of the Atlanta startup ecosystem.

“We think that the Southeast and especially Atlanta has the opportunity to become a key hub for tech startups in the next 5 years. It feels a lot like Los Angeles five years ago. The talent is here but historically the issue has been lack of mentorship, early stage capital, and the later stage capital as they grow and scale,” wrote Outlander co-founder Leura Craig, in an email. “However that is all changing given the fact that so many investors are now moving to all parts of the country and are open to investing in areas that they never invested in before. Covid dramatically accelerated the flight from California and New York and the Southeast’s tech scene is going to be a huge winner as a result of this migration. ”

Major tech companies are also showing their faith in Atlanta’s startup scene through significant investments into the ecosystem. Most recently, Apple has committed nearly $100 million to new projects including the Propel Center, a $25 million bid designed to encourage diversity and entrepreneurship at a site to be built near Atlanta’s Historically Black Colleges and Universities.

It is going to be both a virtual platform and a physical campus in the Atlanta University Center.

Students will be able to follow different educational tracks focused on artificial intelligence, agricultural technologies, social justice, entertainment, app development, augmented reality, design and creative arts and entrepreneurship. This isn’t just a monetary investment for Apple, as employees will help develop curricula and provide mentorship as well. There will be internship opportunities for students.

Apple isn’t the only big tech company to commit to Atlanta’s thriving tech community. Facebook is building out a massive, multi-billion dollar extension to data center facilities near the city, and Google committed that the Atlanta area would receive some fo the planned $9 billion investment in job growth across the U.S.

The current growth that Atlanta’s startup scene is experiencing can serve as a model for other urban areas on the rise. The recipe seems to be a strong technical college, an investment in collaborative startup resources, a network of willing investors to reinvest in the local community, the support of city government through non-profit and promotional activities, and finally an embrace of the diverse history of the city itself. There’s no need to remake Silicon Valley, but the tools of Silicon Valley can be used to make burgeoning tech communities better.

With reporting assistance from TechCrunch analyst Kathleen Hamrick.

Some rising stars of the new Atlanta ecosystem